Page 29 - Contemporary Art and Old Masters

P. 29

After the fall of Isabella II, Joanna I of Castile became the

favourite figure among history painters, who would ignore

historical exactitude to stoke the myth of her madness,

a sign of the prejudices that had accumulated regarding

women and their supposed inability to govern. These images

make it evident that even after the end of the nineteenth

century, recognition of the royal dignity and political power

of women continued to raise representational problems.

THE PATRIARCHAL MOULD

In the late nineteenth century, the State shifted its attention

from history painting onto works of social denunciation, and

to a lesser extent onto the so-called “subjects of the day”,

reflected in scenes that became vehicles for the validation

of customs and the legitimisation of social practices. Within

this second category, there was a particular interest in

girls’ schooling. Although the law recognised the right of

women to a primary education, this remained differentiated

by sexes, a question that drew a string of criticisms from

writers like Emilia Pardo Bazán. Alongside scenes of

girls’ schools, where the pupils were shown being taught

unimportant things with their teachers or classmates, it was

also frequent to find pictures of parents and grandparents

gravely lecturing their daughters or granddaughters on moral

values, and so producing a hierarchical discourse.

In the meantime, the patriarchal message of feminine virtue

also found its way into artistic expression, and the “angel

of the hearth” gave way to more realist images of wives

subordinated to their husbands in the new context of social

painting.

THE ART OF INDOCTRINATION

Some of the works shown in the official exhibitions were

centred on a paternalist notion of the day that women

needed men’s restraint to prevent them from being swept

away by their uncontrollable emotions. Artists interpreted

this supposed emotional nature as part of women’s charm

but also as a sign of their weak character, an idea they

represented in light-hearted images with titles like Pride,

Laziness or Thirst for Vengeance, all clearly critical beneath

their inconsequential appearance. The representation

of madness or witchcraft was used to explore the same

concept, associating woman with states of mental

imbalance or some inexplicable connection with the realm

of the occult and the irrational. However, other artists

preferred to show them enjoying themselves in recreational

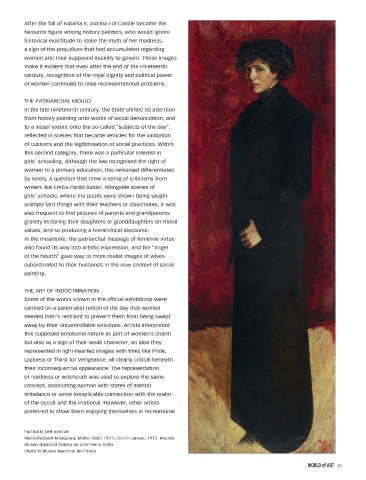

Full Body Self-portrait

María Roësset Mosquera, MaRo (1882-1921), Oil on canvas, 1912. Madrid,

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Photo © Museo Nacional del Prado

WORLD of ART 29